Hi lovely reader 👋

First of all, if you're new here, my name is Sophie. I’m on a journey to slow down, reconnect with nature, and live more intentionally. After moving off-grid, I’m sharing lessons on rewilding, simplicity, and finding balance in a busy world, without any of the fluff.

Join my newsletter if you're also a busy human in need of some balance.

This week I’m bringing you a guest post by . I first came across Louise in this interview where she spoke about connecting with nature when dealing with a chronic illness or disability. I loved her interview (really, go listen to it!) and it prompted me to reach out to her. As my regular readers will know, I love writing about connecting and reconnecting with nature in all its forms. The interview with Louise made me consider how my messaging isn’t necessarily helpful for everyone out there, for example the advice to “just get outside” as you’ll read below. I hope you all enjoy this guest post and find something valuable in here for you.

First of all, who is Louise Kenward?

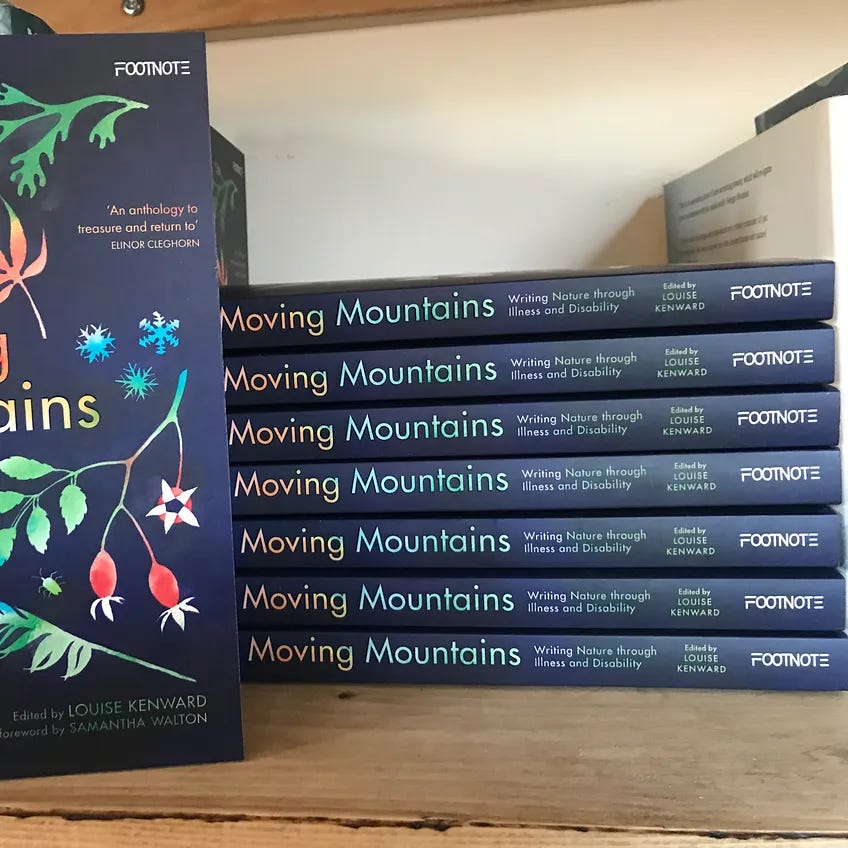

Louise Kenward is a writer, artist and psychologist, and the editor of the groundbreaking anthology, Moving Mountains: writing nature through illness and disability. She was named in the 2023-24 Disability Power 100 list in the UK, and is currently a postgraduate researcher at Manchester Metropolitan University, investigating the shifting coastline of the Romney Marshes. Her work has featured on BBC Radio 3, The Polyphony, The Clearing, and Women on Nature and her first full length book, A Trail of Breadcrumbs, is currently out on submission.

Moving Mountains is an anthology about connecting with nature through illness or disability. The book has been released on 6th May and available now here in NZ. What inspired you to compile this anthology?

When I first articulated the idea of Moving Mountains, I’d been unwell for several years and had developed a renewed connection with the natural world as a result. It was different to how it was before I became sick and I was curious about other people’s experiences who were also sick and disabled. I’d just contributed a piece of writing to the anthology Women on Nature (ed Katharine Norbury) and it had me wondering where the collection of nature writing was by people who lived with chronic illness and disability.

What were some common threads or themes that you found in how the different contributors relate to nature / connect with nature?

I’ve grouped the anthology into themes reflecting ideas each of the contributors drew on - Water, Air, Weather, Earth, Moorland, and Trees - although there are overlaps of course. I’m struck by the association with water especially, and yet can also see that it makes perfect sense. Living with illness I have to adapt and respond to a changing environment (even if that environment is internal), disability and chronic illness demands a kind of flexibility and fluidity that can feel a lot like water.

I think the collection also shows the wide range of experiences of each of the contributors - of their bodies as well as the world around them. While there are a number of connecting factors across the anthology I hope the reader also takes away the vastness of experience, no two pieces are alike.

The reason why I reached out to you for an interview or guest post is because when I heard your interview with Lindsay Johnstone and then subsequently read some of your posts, I realised I’m guilty of what you speak about in your post “air”. As someone who writes a lot about reconnecting with nature I have, on many occasions, given the advice to “just get outside”. I’ve thought a lot about how this isn’t always possible for everyone and one of the reasons this might not be possible is illness or disability, which of course you write about so beautifully.

So I was wondering what advice do you have for those readers who experience barriers to “just going outside” and how can they, to quote you, “catch or capture fragments of the natural world rather than immersing themselves in it”

It’s such an easy thing to say isn’t it, and the advice is everywhere - for people who can ‘just get outside’, it feels like the simplest thing to do. For those who can’t, it’s often the thing they most want to do, and can feel incredibly frustrating and a deep loss. There’s an enormous amount of grief that comes with chronic illness, and any kind of acquired disability (and 80% of disability is acquired, through illness or injury, for example), so I’m hoping that beginning to normalise this more will help with adjustment for people ‘not yet’ disabled. It’s a marginalised group that most of us are likely to join at one time or another. The additional shame and stigma that burdens us is an added labour we could do without. Getting sick and developing a disability is a normal part of life. There are enough things to negotiate in living with a newly disabled body, rather than deal with anything else that society imposes.

In terms of advice, I think everyone has their own interests and ways of navigating the world they find themselves in, but to share my own experiences, I’ve found a range of things helpful at different times. Depending also on what is outside of your bedroom window, or in your garden, if you have one, listening to birdsong is a popular way of engaging with the natural world - something I’m doing as I write this, while in bed with the window open. There are all kinds of apps and online tools to learn the songs from different birds around the world now too, if you are able and interested in finding out more. You can get bird feeders that attach to the window if you want to encourage them closer and watch them from your bed/sofa. Polly Atkin (one of the contributors to Moving Mountains) writes about Dorothy Wordsworth in her book Recovering Dorothy, and how she left her windows open, adopting a robin who would visit her in bed.

I also have collections of objects I reference in my creative piece in the anthology ‘Things in Jars’, pebbles and bits of driftwood and crab shells I’ve brought back from the beach on previous trips. My energy-limiting conditions fluctuate, which means that sometimes I am/have been able to get outside, so bringing back mementoes of these trips means I have tactile memories to draw on when I can’t get out. I ran a workshop for the Festival of Nature (online) last year and found that everyone in the group similarly had objects like this on their desks or bedside tables. It was a really lovely session where we all ended up sharing our favourite objects at the end. When I have less energy but am able to watch a screen, I love to find new webcams. I learned to scuba dive when I had a period of remission, so I love to find webcams of the deep sea research subs, listening to the scientists' conversations about what they can see, watching for life on the ocean bed. I try to share new sites of webcams I find and have written several substack posts with links to these and other accessible/online sites that offer experiences you wouldn't get in person too.

I’ve just found the Underwater Manatee Cam at Blue Spring State Park, and am reminded of the worldwide network of cameras around the planet, EXPLORE, which shows the natural world in real time across the continents. The sound of the manatees swimming and the slowness of their movement is wonderfully hypnotic.

This is becoming quite a long answer, but this is the first year in I can remember that I’ve planted seeds - planting seeds and bulbs at a time when the days are dark and cold brings exciting (for me) days to look forward to, when I’ve forgotten what I’ve planted and new early shoots begin to emerge. It’s all a reminder, at a deeper level, of the circle of life and the necessity of periods of darkness and hibernation.

What small, short, easy nature connection practices did you discover through the anthology that might work for people with limited mobility or energy?

This is probably the same answer as the last question, but the solidarity in reading and knowing that so many other people share the experiences I have of limited mobility was enormously valuable.

How can people adapt their relationship with nature during periods when they can’t physically access outdoor spaces?

There will be multiple ways depending on what you find of interest and what you were interested in before - there are lots of online sites for watching and listening to outdoor spaces beyond your front door, and being online means that you can travel further than you might have done when you could get outside. I know screens aren’t always accessible for people (which is why I always audio record my substack posts), so when I find looking at a screen difficult I enjoy listening to the radio. There are lots of podcasts and programmes which follow people on walks, or talking about different aspects of the natural world. Audio books are also something I have used a lot when I’ve not been able to read a physical book.

Abi Palmer is perhaps the best example in Moving Mountains, of how we adapt our relationship to nature, as she brought nature indoors - creating weather for her cats Lola Lola and Cha-U-Kao, who similarly were not able to get outside (both house cats living in a flat in London). ‘Abi Palmer Invents the Weather’ is an essay and transcript of a series of films she made of the same name, creating fog, light, heat and rain, for her cats to enjoy. A commission from the World Weather Network, supported by an ArtAngel grant, it’s a beautiful and humorous way of bringing in more complex ideas about the environment. The films are currently travelling galleries around the world and can also be seen online.

How did you, or any of the authors who contributed to the anthology, reframe your/their relationship with nature?

The change in relationship with the natural world is something that was most marked for me when I lost contact with the human one. Sick in bed for more than a year, it was the change in light that I noticed most. It gave me a frame of reference for the world around me that I couldn’t get elsewhere (or the most meaningful one) - I could chart the changing time and changing seasons as the sun moved across the horizon. It’s made me, as I think it does for others in the anthology, much more conscious of our existence as being a part of nature, not separate from it. I think this adjustment, to seeing nature as within us and vice versa, is important to seeing its relevance to us - both in considering disability but also in considering the natural world and the environment (all of which is in need of greater care and respect).

What do you hope readers take away from this post, and from reading Moving Mountains?

I wanted to make the book work on two levels - for those who live with illness and disability, I wanted to bring a sense of solidarity and companionship, for those who do not (or who are not yet disabled) I wanted to show the diversity of disability and range of engagement with the natural world that is possible. My hope is that it will challenge ideas of nature as well as disability, and will offer a new way of thinking about the human and more-than-human world - one in which there is less shame and stigma in developing disability.

This Is Sophie Today is a reader-supported publication and while all posts are free, I need your support to keep this going. If you’re enjoying what you’re reading, consider picking up a paid subscription. A monthly subscription is 5 NZD or 2.8 USD and a yearly subscription is 45 NZD or 25 USD.

Thanks for sharing this interview Sophie. It left me with new perspectives to consider around in/accessibility to nature and even to screens. I create nature soundscapes on youtube to bring nature into the home, and lately I have been thinking about how these can be helpful in health care and aged care facilities. Lots to think about 🙏🌿

Thanks for the interview / guest post, so interesting!! I loved the many ideas how to connect with nature anyway. 🌿